Saturday, September 09, 2006

Serious Play

Friday, September 08, 2006

In Praise of the Ad Hominem Argument...Maybe

Thursday, March 02, 2006

The Glass Really Is Half Empty...But Must It Be That Way?

ABOUT HALF OF BUSINESS DECISIONS END IN FAILURE, STUDY FINDS

COLUMBUS, Ohio -- Managers fail about half the time when they make business decisions involving their organization, a new study suggests.

About one-third of real-life business decisions studied by an Ohio State University researcher were initial failures -- the decisions were never implemented by the organizations involved.

The failure rate climbed to 50 percent when the researcher considered decisions that were only partially used or that were adopted but later overturned.

"These figures suggest that enormous sums of money are being spent on decisions that are put to full use only half the time," said Paul Nutt, author of the study and professor of management science at Ohio State's Max M. Fisher College of Business.

"Managers need to look for better ways to carry out decision making."

These results come from a unique database of 163 business decisions compiled over 16 years by Nutt, who is author of the book Making Tough Decisions (Jossey-Bass, 1989). The database includes decisions by managers at private firms, government agencies, and non-profit organizations. In each case, Nutt asked a top-ranking official of the organization to suggest a decision involving the organization and to name two executives who were familiar with the decision and responsible for carrying it out.

The decisions could involve anything -- from purchasing equipment to renovating space to deciding which products or services to sell.

Nutt conducted in-depth interviews with the two officials selected, asking each to spell out the sequence of steps that were taken to carry out the decision-making effort.

After the interviews, Nutt provided a written summary of the decision-making process to each of the officials involved so they could check it for accuracy.

A decision was classified as an initial failure if it was never adopted by the company. For example, a decision to merge with another company was a failure if the merger was never completed. Nutt found that 36 percent of decisions fell into this category.

A partial failure occurred when only some part of the decision was adopted. An ultimate failure occurred when a decision was adopted but later withdrawn by the organization. When he excluded partial or ultimate failures, Nutt found that only 50 percent of decisions were successful.

Nutt has since expanded his database to 376 decisions, each involving a separate organization. Although he has not finished analyzing the new data, preliminary results suggest the general picture is the same -- 40 percent of the decisions in the expanded database resulted in initial failures.

Nutt cautioned that the decisions he has studied are not a true random sample. He began the search by asking corporate officials he knew to participate. These officials would then recommend other people. Also, the decisions studied were chosen by the organization officials themselves and were not randomly selected.

But Nutt believes a true random sample may show the decision failure rate to be even higher. "I think that corporate leaders would be more likely to tell me about successful decisions at their organizations than they would unsuccessful decisions," he said. "So the real figures may even be worse."

Why do so many business decision fail? Nutt said that managers often use the least effective decision-making tactics. One of the things Nutt analyzed was how managers implemented their decisions. He found that the most successful implementation tactic involved asking for the participation of those who would be affected by the decision. That tactic had the lowest failure rate (30 percent). But it was the least used tactic, being used in only 23 percent of the decisions Nutt studied.

In contrast, one of the most used implementation tactics -- in which managers simply issue directives about how they want a decision implemented -- was the least successful. It was used in 30 percent of the decisions studied, but had a failure rate of 64 percent.

Nutt said he believes most managers know effective decision-making tactics, but don't feel they have the time or resources to put them to use.

"Most of the good decision-making tactics are commonly known, but uncommonly practiced," he said. "Managers seem committed to fast answers and fail to recognize that quick fixes make failure likely."

This study will be included as a chapter of the book Making Successful Strategic Decisions, which is scheduled to be published next year by Sage.

Contact: Paul Nutt, (614) 292-4605; Nutt.1@osu.edu

Written by Jeff Grabmeier, (614) 292-8457; Grabmeier.1@osu.edu

If You're So Smart

I, Laius, faced my deposer. "Well, son, one million plus one million is two million."

With eyes as large as saucers, my son responded, "Wow! You are good."

There are at least a couple of lessons here for all of us to learn.

- A little bit of knowledge can make us both dangerous and foolish. The Apostle Paul said that "...knowledge puffs up...". My experience is that the amount of puffery seems inversely proportional to the amount of actual knowledge we possess - the more you posture what you know, the less you actually know. When you think you are going to undermine someone with what passes for less than a novice level of apprehension of what is so, prepare yourself for a fall. And quite frankly, you will deserve it.

- There is typically much more complexity associated with that which is so than we like to admit or are even capable of recognizing. Unfortunately, we tend to believe that simplest is best. When it comes to making decisions, we rely on linear explanations and single point assumptions to guide our thoughts. When we're this simplistic, we miss the opportunity to explore the richness of underlying causes and effects that can make us regret our commitments or reap previously unconsidered sources of value.

It seems paradoxical, but there is value hidden away in uncertainty, and there is value in exploring it. When we're so smart, we admit we're ignorant, and we take the steps to explore and to correct it.

A Girl Named Bright

There once was a girl named Bright/ Whose speed was much faster than light./ She set out one day/ In a relative way/And returned on the previous night.

Then I felt a wave of nausea that usually accompanies an intense feeling of cognitive dissonance. My sense of reality became up-ended. "The speed of light not a barrier?" I thought to my self. This cannot be. Certainly someone is mistaken.

The established ultimate boundary of cosmic speed was more than just a fact to me. From as early as I can remember, the exact speed of light (299,792,458 meters/second) was dear. I knew this number better than my girlf friend's telephone number (Yes, I had a girl friend, but she thought I was a geek, too.) Like many other physics students before me, I used to lay awake at night pondering the gedanken of Herr Einstein, wondering just what my experience would be were I to travel through the Minkowski space-time continuum at such breakneck speed. Collapsing light cones! Lorentz time dilation! Mass dilation! Dopplegangar paradoxes! Yes, I've invested emotion into this. As a former physics teacher, I've taught this...nay, I've preached this...with conviction from my pulpit. This was as solid as my grand mother's love or the ground beneath my feet. On June 5, 2000, as I reread the article, I think my universe changed, and dramatically so.

Understand what I'm saying. To say that nothing can go faster than itself is a truism. The proposition is internally self-consistent (like A=A) and requires no emperical evidence to be accepted as true. It is merely an extension of such a general statement to say that light cannot go faster than itself. We are still in the realm of statements that can be accepted without question. While incontrovertible, though, they are not particularly interesting. But to say that nothing can exceed the speed of light is an altogether different kind of statement. We do not say this because we have tested every particle in the universe to see which ones can or cannot exceed the speed of light. Although we have accumulated some body of experimental data and mathematical constructs that strongly imply that to say, "Nothing can exceed the speed of light" is acceptably true, there really is no definite empirical evidence that it is true. But although the evidence is strong, to believe it without a moment's reflection requires either a type of faith or omniscience, of which none of us possess the latter. (For another interesting article on the subject of the speed of light and the possibility that it might not represent the ultimate speed, visit here.)

I'm choosing my words carefully at this point. I did say "faith." Don't fall into the popular misconception that faith is the belief in something without any evidence, a type of prejudice or presupposition. Quite the contrary. For centuries, theologians have used the term "faith" to mean the belief in something that cannot be seen based on the evidence of things that have been experienced, particularly in this context, through past interations with God. But to ease things up a bit, I'll paraphrase the venerable Reverend Bayes, a man of faith (and a Calvinist, too, for those of you "determined" not to listen): knowledge about the state of our environment is subject to uncertainty and ambiguity. Absolute certainty can only be obtained through omniscience.

Please, do not misunderstand what I'm saying. I would not go so far as to say that there is nothing that can be known or that we cannot know anything other than our own existence (a sort of Cartesian naked singularity). I fear such an unresolvable solipsism as much as the next guy. Something about our experience is rooted in some objective reality. Even if we cannot truly see IT, something about IT is being transduced through our senses to our consciousnesses. What I am saying, though, is that knowledge and information, from the raw, pure data we collect by Popperian methods to the natural common sense we regress with our experiences and senses, should be regarded as possessing a degree of ambiguity, uncertainty, and bias (both cognitive and motivational); and we should always (dare I now use such an absolute adverb?) regard it as such. I think not only humility dictates it, but as of June 5, 2000, the Sunday Times seems to dictate it.

This discussion could lead down numerous pathways, and I would love to discuss them all with each of you. The conclusion I want to emphasize is the need to include a healthy understanding of the uncertainty and our biases involved in any major decision situation at hand. In all seriousness, I do not think that the speed of light should be regarded as an uncertainty. In fact, although I may be quite wrong, I feel reasonably sure that the questions regarding the speed of light apply to "special" cases, the effects of which do not dominate in most daily situations. But if something as resolutely established as the inexcessible speed of light can be brought under serious cross examination, imagine the myriad "facts" we think we know by which we guide our decision-making that have never been confirmed by so much as a sigh from Mt. Sinai or even one controlled experiment.

Indifference and Fixed Resources

I called my friend, George P. Burdell, a man known for knowing specifically what to do, and related my friend's situation and generic disposition. After thinking for a while, George responded, "If your friend will do anything, he won't do nothing." We Southerners often resort to double negatives to emphasize the point.

I think we've all heard repeatedly that we have to differentiate our services and our selves in order to be successful in business. This probably couldn't be more true than in professional services. However, have you ever really wondered why this might be true other than a matter of distinction? I found an interesting explanation this week in one of the books I'm currently reading: Armchair Economist: Economics And Everyday Experience by Steven Landsburg.

In Chapter 4, Landsburg discusses the Indifference Principle and Fixed Resources. To understand how the indifference principle works imagine a hypothetical restaurant staffed by hypothetical busboys and janitors. The distribution of busboys to janitors is determined in part by each person's preference for combination of pay wages, schedule, level of effort, etc. The distribution would remain more or less fixed for a given set of parameters at the point at which people are indifferent to the parameters. However, if people start tipping busboys, busboys' wages increase, and janitors start wanting to become busboys because the wage parameter that contributed to making them indifferent to another line of work has shifted.

The result of the Indifference Principle is that "...when one activity is preferred to another, people switch to it until it stops being preferred (or until everyone has switched...). Second is its corollary: Only fixed resources generate economic gains. In the absence of fixed resources, the Indifference Principle guarantees that all gains are competed away."

Prior to this, Landsburg pointed out that "...Only the owner of a resource in fixed supply can avoid the consequences of the Indifference Principle. An increased demand for actors cannot benefit actors because new actors are drawn to the field. But an increased demand for Clint Eastwood can benefit Clint Eastwood because Clint Eastwood is a fixed resource: there is only one of him."

In other words, differentiation is what makes us a fixed resource as opposed to competing for diminishing marginal gains. Being a fixed resource makes us appreciably different. A lot of things will make us stand out, but being a fixed resource makes us valuable.

Does that strike you as obvious, or is that a slightly different way of thinking about why differentiation is so important?

I think the question, then, for myself is: "how do I do this?" How do I become a fixed resource? In some ways, it is the nature of of the service I provide that accomplishes some of that, but I'm sure there are many more intangible qualities as well.

What do you think makes you a fixed resource?

Wednesday, January 18, 2006

Colored Bubbles and Knowing What to Do

I'll wait a while for you to read it. Would you like a cup of tea?

It really is an amazing story of determination and ingenuity. Tim Kehoe wanted colored bubbles, not an easy technical task. Ultimately, Ram Sabnis, a dye chemist, gave him colored bubbles. All it required of Sabnis, of course, was for him to invent a new dye chemistry. That's all.

Hmmm.....I need a flux capacitor. You know, so I can travel back in time.

The flux capacitor is what makes time travel possible. It requires 1.21 jigawatts of electricity to operate.

I'd borrow shares on October 23, 1929 to short sell the next few days. The world would be my shrimp; I, its Forrest Gump, raking it all in by the nets full. Bwahahaha! Any unemployed physicists out there willing to join me on the high seas of temporal adventure for fun and profit?

Of course there is quite a difference in using the existing rules of nature to do something extraordinary versus violating the laws of nature to do something opprobrious. The latter effort is just wrong...on both accounts.

But an insight came across my mind as I read the article: given enough time, money, and intelligence, we can do anything we want to do! Our universe is plastic, submitting to our minds and malleable in our hands to accomplish that which we desire. If we want colored bubbles, we can have them.

I immediately thought of my friend, visiting scholar, and great American, George P. Burdell, a man known for his time, money, and intelligence. I called him and hurriedly conveyed my new found insight. I waited with pregnant expectation for his approval. There was a long pause.

"Yes, that sounds true enough. But the real wisdom, it seems, is in knowing what to do."

Monday, January 16, 2006

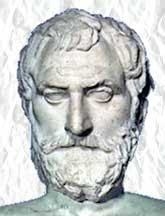

Why "Thales' Press"?

Apparently, Thales was ridiculed for being poor as a result of his pursuit of truth as opposed to wealth. Thales contended that he wasn't concerned with wealth, but he could use his wisdom to achieve wealth if he wanted to. To prove that he wasn't just whistling The Odyssey, he employed his knowledge of astronomy and other observations to determine that there would be a huge crop of olives in the upcoming harvest (How did astronomy play in this calculation? I haven't a clue.). Using what resources he had, Thales then purchased for a small amount of money the right to lease local olive presses during the harvest time. When the huge crop came in as he predicted, Thales cornered the market of olive presses, leased the presses back out at a higher rate, and made a substantial sum of money. Not only was Thales likely the first natural philosopher, he was also likely the first decision analyst.

Not only did I adopt the title "Thales' Press" to refer to this historic use of systematic reasoning to achieve some goal (namely, the acquisition of olive presses to make a bunch of money), I also intend to press the use of the word "Press" to refer to a means of publishing. The publishing being focused on considerations and observations by myself and others (visiting scholar, George P. Burdell, a great American, may contribute on occasion) about decision analysis and decision management.

About Me

- Robert D. Brown III

- Atlanta, Georgia, United States

- I am a senior decision support advisor who provides guidance, deep insights, and valuable solutions for senior decision-makers facing complex, high-risk problems related to strategic planning, risk management, project valuation & planning, and project portfolio analysis & management. My goal is to help people ensure that the decisions they make are well framed (focused on the right problem and clearly defined) and that they understand the implications of uncertainty and risk on the likelihood of achieving their goals.

Contact Me

Business Case Analysis with R: Simulation Tutorials to Support Complex Business Decisions

Check out our tutorial on using the statistical programming language R to conduct business case analysis and simulation and a little bit more.

"A decision was wise, even though it lead to disastrous consequences, if the evidence at hand indicated that it was the best one to make; and a decision was foolish, even though it lead to the happiest possible consequences, if it was unreasonable to expect those consequences."

~Herodotus, ca. 500 BC.

Meetups

Blogs I Follow

- Accidental Creative

- Bleeding Heart Libertarians

- Cafe Hayek

- Eliezer S. Yudkowsky

- Gerald Weinberg's Secrets of Writing and Consulting

- Indexed

- Library of Economics and Liberty

- Nicky Case

- Overcoming Bias

- Popehat

- Science Daily

- Slate Star Codex

- Slightly East of New

- Storytelling with Data

- The Great Decide (no recent updates)

- Understanding Uncertainty

Recommended Reading

Ask, Inspire, Solve.: The Science and Practice of Facilitative Questioning

Bayesian Methods for Hackers: Probabilistic Programming and Bayesian Inference

Business Case Analysis with R: Simulation Tutorials to Support Complex Business Decisions

Business Portfolio Management: Valuation, Risk Assessment, and EVA Strategies

Certain to Win: The Strategy of John Boyd, Applied to Business

Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors

Data Analysis: A Bayesian Tutorial

Decision Analysis for Managers: A Guide for Making Better Personal and Business Decisions

Decision Analysis for the Professional

Decision Quality: Value Creation from Better Business Decisions

Decision Traps: The Ten Barriers to Decision-Making and How to Overcome Them

Doing Bayesian Data Analysis, Second Edition: A Tutorial with R, JAGS, and Stan

The Failure of Risk Management: Why It's Broken and How to Fix It

The Flaw of Averages: Why We Underestimate Risk in the Face of Uncertainty

Foundations of Decision Analysis

Game Theory 101: The Basics

Game Theory for Business: A Primer in Strategic Gaming

Handbook of Decision Analysis

How to Measure Anything: Finding the Value of Intangibles in Business

How to Measure Anything in Cybersecurity Risk

An Introduction to Bayesian Inference and Decision

Making Hard Decisions: An Introduction to Decision Analysis (Business Statistics)

Mistakes Were Made (but Not by Me): Why We Justify Foolish Beliefs, Bad Decisions, and Hurtful Acts

Monetizing Your Data

Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game

Psychology of Intelligence Analysis

Risk Savvy: How to Make Good Decisions

The Signal and the Noise: Why So Many Predictions Fail--but Some Don't

Simple Heuristics That Make Us Smart

Smart Choices: A Practical Guide to Making Better Decisions

The Smart Organization: Creating Value Through Strategic R&D

Thinking, Fast and Slow

Thinking in Systems: A Primer

Thinking Strategically: The Competitive Edge in Business, Politics, and Everyday Life (Norton Paperback)

Uncertainty: A Guide to Dealing with Uncertainty in Quantitative Risk and Policy Analysis

Value-Focused Thinking: A Path to Creative Decisionmaking

Why Can't You Just Give Me The Number? An Executive's Guide to Using Probabilistic Thinking to Manage Risk and to Make Better Decisions

Why Decisions Fail

You Are Not So Smart: Why You Have Too Many Friends on Facebook, Why Your Memory Is Mostly Fiction, an d 46 Other Ways You're Deluding Yourself

You Are Now Less Dumb: How to Conquer Mob Mentality, How to Buy Happiness, and All the Other Ways to Ou tsmart Yourself